A new report released Wednesday shows the use of fake internet domain names to trick consumers into giving up personal information is more widespread than experts originally thought.

Using fake internet domain names to get consumers’ personal information is a more popular hacking technique than we thought.This is largely because of the heightened use of Internationalized Domain Names (IDNs), which use homographs carefully crafted to look exactly like their English counterparts. Hackers create domain names that replace an English-language character with a look-alike character from another language — replacing the Latin letter ‘a’ with the Cyrillic letter ‘a,’ for instance — as a way of luring users to fake websites where they’re prompted to enter their personal information.

The report from cybersecurity firm Farsight Security identified 125 different websites, from social networking giants like Facebook and Twitter to luxury brands like Gucci and financial websites like Wells Fargo, being imitated by fake domain addresses. Between Oct. 17 and Jan. 10, the group observed more than 116,000 imitator domains of these sites in real time.

Security systems are often unable to detect this problem before the hack occurs, the report also found.

“This problem got worse than we thought it could, faster than we thought it could,” said Paul Vixie, Chairman and CEO of Farsight Security and one of the developers of the Domain Name System that configures IP addresses into readable domain names.

Why were IDNs created?

Scammers have used fake or confusing domain names since the start of the internet. But with the introduction of IDNs in May 2010, the problem became much more widespread.

Developers created the Internationalized Domain Names (IDN) system to bridge the gap between English and non-English speakers using the internet. It allows anyone to create and register domain names using character sets in various languages.

But cybercriminals also use the IDN system to lure consumers to phishing websites that appear exactly like the ones they intended to visit.

“It’s now being used in spite of the prior knowledge of the experts, it’s now being broadly abused against top domain names,” Vixie said.

Vixie said that when DNS was first released it was not secure enough to be used by everyone who wanted to access the internet.

“It got out of the lab and into people’s pockets a decade or so sooner than it should have been allowed to,” he said. “But I guess there’s money to be made so we made it.”

How it works:

Take a popular financial site like BankofAmerica.com. Cybercriminals take this domain and change one character, like the Latin letter ‘a’ to a similar Cyrillic letter ‘a’ — and create a website that looks strikingly similar to the original Bank of America page.

A user types in their login information and password on this fake Bank of America site, automatically giving cybercriminals their credentials to log in to the real thing. IDN homographs are also sometimes used to introduce spam or malware on a user’s device.

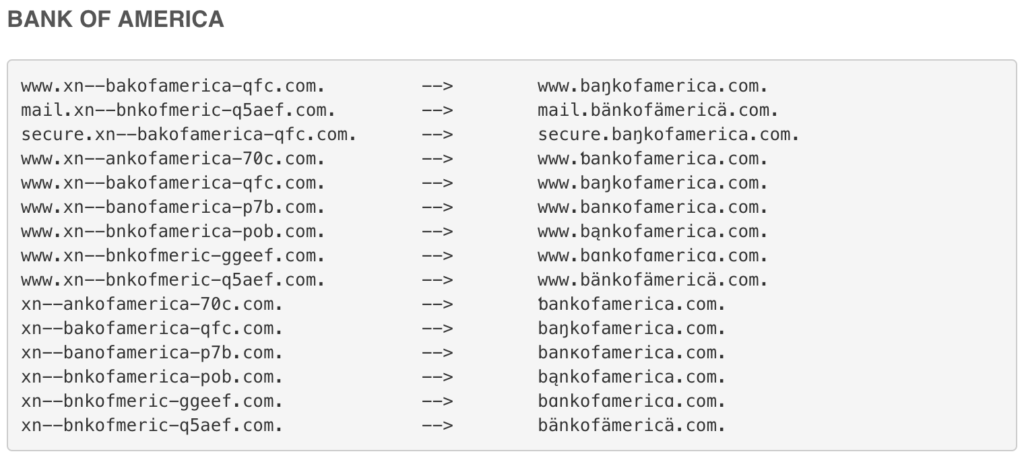

Below is a list of suspicious IDNs that Farsight Security identified mimicking the original Bank of America site:

Above, the left column shows how hackers enter look-alike IDN homographs “under the hood”. The right side shows how the same domain name would actually appear to the average user in a web browser or email hyperlink.

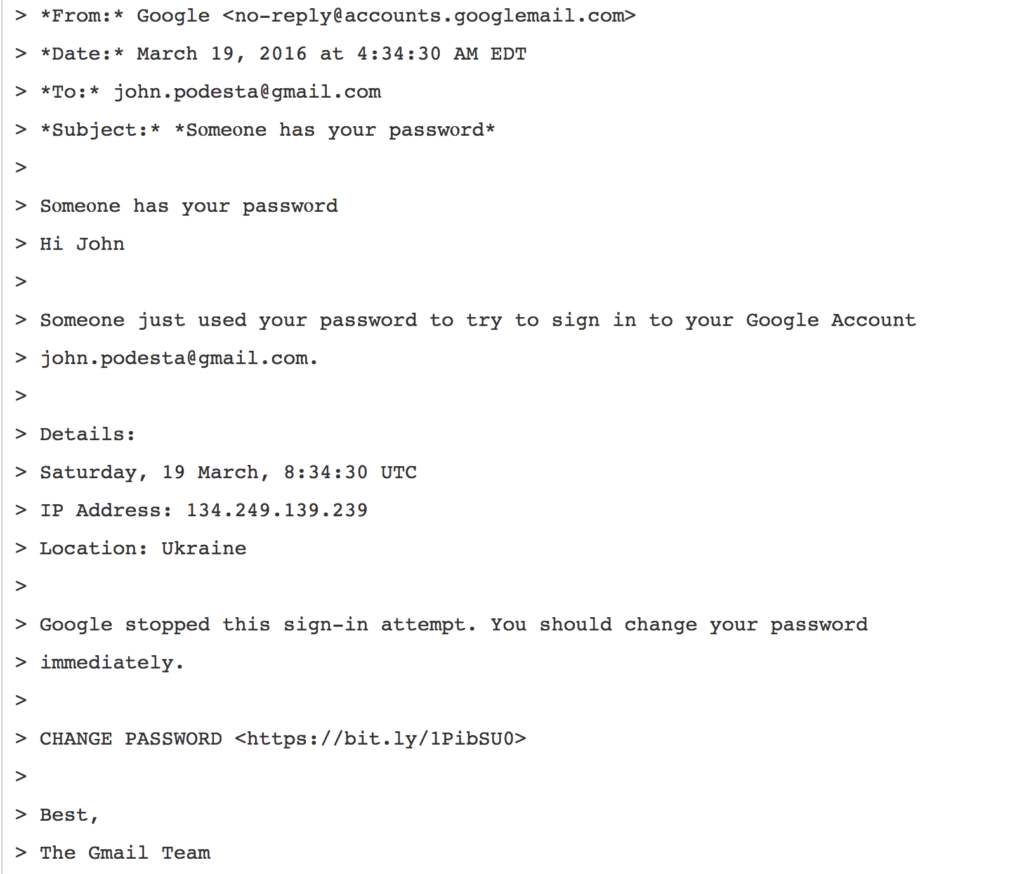

A famous example is the phishing email Clinton campaign chairman John Podesta received in 2016, claiming a Google user had tried to access his account. It included a link for him to change his password. Podesta followed the link and changed the password, giving hackers access to his entire Google account, CNN reported.

Many email providers scan messages for the word “password,” since this is often used in malicious emails, according to the International Data Group (IDG). Providers like Google will often attach a warning to the email, indicating it looks like spam. But if the word “password” is written with a Cyrillic “o,” like in the email John Podesta received, the message will slip through the filter. Homographs were combined with other advanced attack email methods during the Democratic National Convention hack, according to the IDG.

Below is the copy of the email Podesta received, obtained by Wikileaks:

A phishing email directed toward John Podesta, former chair of Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign. The email was obtained by WikiLeaks.

Who is behind these attacks?

Russian government hackers were behind the Democratic National Convention computer break-in, which gave them access to the database of opposition research on Donald Trump, Crowdstrike co-founder Dmitri Alperovitch told the PBS Newshour in June 2016. Crowdstrike investigated the intelligence breach for the DNC. The Russian government denies involvement.

Some of the threats may be linked to nation-states, but the majority of attacks via IDN homographs comes from lone cybercriminals, said Rick Holland, Vice President of Strategy at Digital Shadows, an oversight group that monitors and remediates security risks on the internet.

And while sometimes the target is a nation at large, it’s really the “people that are in our individual circles in our life that are likely to be impacted by this; it’s going to be from a cybercriminal that’s using IDNs to steal money from my dad,” Holland said.

How you can protect yourself

Fortunately, most common website browsers like Google Chrome and Mozilla Firefox already have security measures to notify users that they may be visiting a suspicious website. But last April, security researcher Xudong Zheng found these browsers could not flag a fake domain name for “аррӏе.com” that used all Latin look-alike characters from the Cyrillic alphabet.

Most phishing attempts reach internet users through email, so you should be suspicious of any emails that include “distressing or enticing statements to provoke an immediate reaction” or login links to different accounts combined with demands to update information, the Farsight Security report warns.

Enable the safe browsing feature and watch the URL as it loads.The report also warns that you should enable the safe browsing feature if it available and watch the web browser as it loads. For sites that request a password, the URL should begin with “https://” instead of “http://” — or, the browser should display a green padlock sign. Watch the URL address to ensure that it does not change unexpectedly after clicking on the link, and enable two-factor authentication for all websites that support it.

It is also important to be familiar with how a browser handles IDNs in general, according to the report. Chrome has a page here explaining the process.

What’s next?

Experts say this problem will only get worse because ordinary people are not sure how to protect themselves or are not thinking about it when they are online.

Tech companies like Google are doing what they can to ensure this does not happen to their users, Vixie said, but there is no simple software or 10-step process to entirely avoid becoming the victim of a phishing scheme.

“There is simply no silver bullet that can fix this overnight.”“This problem can’t get technically fixed once and for all, there is simply no silver bullet that can fix this overnight,” said Thomas Rid, a professor of strategic studies at Johns Hopkins who was not involved in the study. Rid said one way to prevent becoming a victim to a phishing scheme is to simply not click on any link you think is suspicious.

But Holland thinks the security community can do more to protect consumers. He thinks that content and network providers should do more to identify suspicious activity. “In the age of big data, the capabilities exist,” he said.

“We should be embedding security measures in these browsers and enabling them by default, not making you have to add something else,” Holland said, adding that two-factor authentication should be enabled automatically for all public-facing applications.

“It’s going to be status quo or get worse, because for the 90 percent of regular people out there that just aren’t sure what to do, there is not transparent enough security in place to help them.”

ncG1vNJzZmivp6x7sa7SZ6arn1%2Bjsri%2Fx6isq2eelsGqu81on5qbm5q%2FtHnAq5xmnpykvKW1zaBkraCVYravwMSrpZ6sXay2tbSMpqarnV2brqyxjJ2mppmZo3qvrcyeqmaglaeytHnHqK5msZ%2BqeqStzWanq6ekmrC1ediorKurlaGz